Take me to the river

Based on 2 Kings 5:1-14 & Mark 1:40-45

I don’t often find time to read novels, so it’s a real treat whenever I so.

And one I particularly liked was ‘The Needle’s Eye’ by Aotearoa New Zealand

author Errol Braithwaite, which I first read when I was 16 or

17.

This is a historical novel set in the Waikato Wars in the 1860s. It is

memorable for many reasons. It gives a sympathetic and well rounded

presentation of both Māori and Pākehā perspectives. Which was quite rare for

Pākehā authors of the day. It has strong characters. And it’s a gripping

story.

When I was part way through it, I learned it was the second

part of a trilogy set in the Taranaki and Waikato wars and decided I really

should read all three books in sequential order. But that never happened

until about twenty years ago, when I found the complete set in Bookstacks, a

second hand bookshop that used to be in the Raumati Beach village, which

some of you will remember. And this time I read the entire trilogy.

The first instalment, ‘The Flying Fish’, was particularly memorable. Partly

because it was largely set in my home town of Ngāmotu New Plymouth and there

were references to rivers, hills, and streets that I not only knew but knew

very well. But it also built the foundation on which its successors were

built. So by the time I got to re-reading ‘The Needle’s Eye’, I had a much

better appreciation and understanding of Major Williams, the central

character. And this was even more enhanced when I got to the final book,

‘The Evil Day’.

Often, things just need to be read in the right order.

In Anglican

churches, we have usually have four

readings set down for each morning of the year, albeit with some options.

These readings typically comprise an Older Testament lesson, a Psalm (which

is often sung or chanted), a Newer Testament Epistle reading, and finally

the Gospel.

Like many churches, we usually omit the Psalm and we have three readings.

But some churches don’t even have that many; I have been to churches where

there were only two readings. Sometimes only one. It is very common for

churches to overly emphasise the Newer Testament over the Older Testament.

And I am guilty of this. Mainly to save weight, I will often carry a Newer

Testament with me. But rarely a complete Bible.

There have even been occasions in my preaching career when priests (none of

whom are here today or presently in our parish) have been unhappy because I

chose to preach about the Older Testament lesson of the day; on one

occasion, the presiding priest seemed adamant we should always preach about

the Gospel, without exception.

But while the Older Testament preceded the Newer Testament and it not yet

been compiled when Jesus taught or even during the first few hundred years

of the Church’s existence, its contents were well known and studied in

Jewish religious circles in Jesus’ day. It was the scripture Jesus knew and

taught from. And often – such as today – our Older Testament Lesson is

directly related to our Gospel reading, and it adds meaning and context that

would be otherwise lacking.

Now you may be wondering why I habitually use the terms Older and Newer

Testament instead of Old and New Testament. There are two reasons for this.

The first is that the usual naming convention seems to imply the Older

Testament is secondary. And the second is that they are BOTH old.

I should also point out that many of most interesting parts of the Bible are

in the Older Testament. Now seem of it can get a bit tedious; the first nine

chapters of the First Book of Chronicles are genealogy. That’s nine

consecutive chapters. But parts of it are quite action packed; apparently

the Book of Judges is the most the most violent book in the Bible. Someone

spent time working that out.

And parts of the Older Testament are quite racy. While you might may

automatically think of the Song of Solomon, but that is very tame compared

with some parts of the Book of Ezekiel.

Interestingly, there is no consensus as to how many books there are in the

Older Testament. It varies between different denominations of the Church. But

that’s a conversation for another today.

Today’s Older Testament Lesson is from the Second Book of Kings. Which is

one pf the Older Testament books that is universally accepted by the Church.

The two Books of Kings were originally a single volume, as were the two

Books of Samuel. Along with the Books of Joshua and Judges and the First and

Second Books of Samuel that precede them, they comprise a section of

scripture that the great German scholar Martin Noth named the Deuteronomic

History. He argued that these books were in fact created by a single author

and complier in the 6th Century BCE, who attempted

to use the theology and language found in the Book of Deuteronomy to make

sense of recent events, notably the conquest of Jerusalem and the Babylonian

exile.

While later scholars have revised some of Noth’s conclusions, notably,

setting the time of composition as beings lightly earlier but with some

later redaction, the concept remains essentially sound.

The Deuteronomic History follows the story of the Jewish people from the

death of Moses to the release of the last king of Judah in captivity in

Babylon. The books it comprises are known as the Former Prophets to Jews,

and along with the Books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Twelve Minor

Prophets, they comprise the Nevi'im or The Prophets in the Tanakh, or Hebrew

Bible, whose composition was finalised in response to the Church’s

compilation of the Older Testament. While the Jewish scriptures had existed

for some time, there had been no previous consensus as to what was in and

what was out. Just like there is no consensus today in the Church as to what

is in the Older Testament.

There are many things we can learn from today’s Older Testament Lesson, and

I will note just three of them.

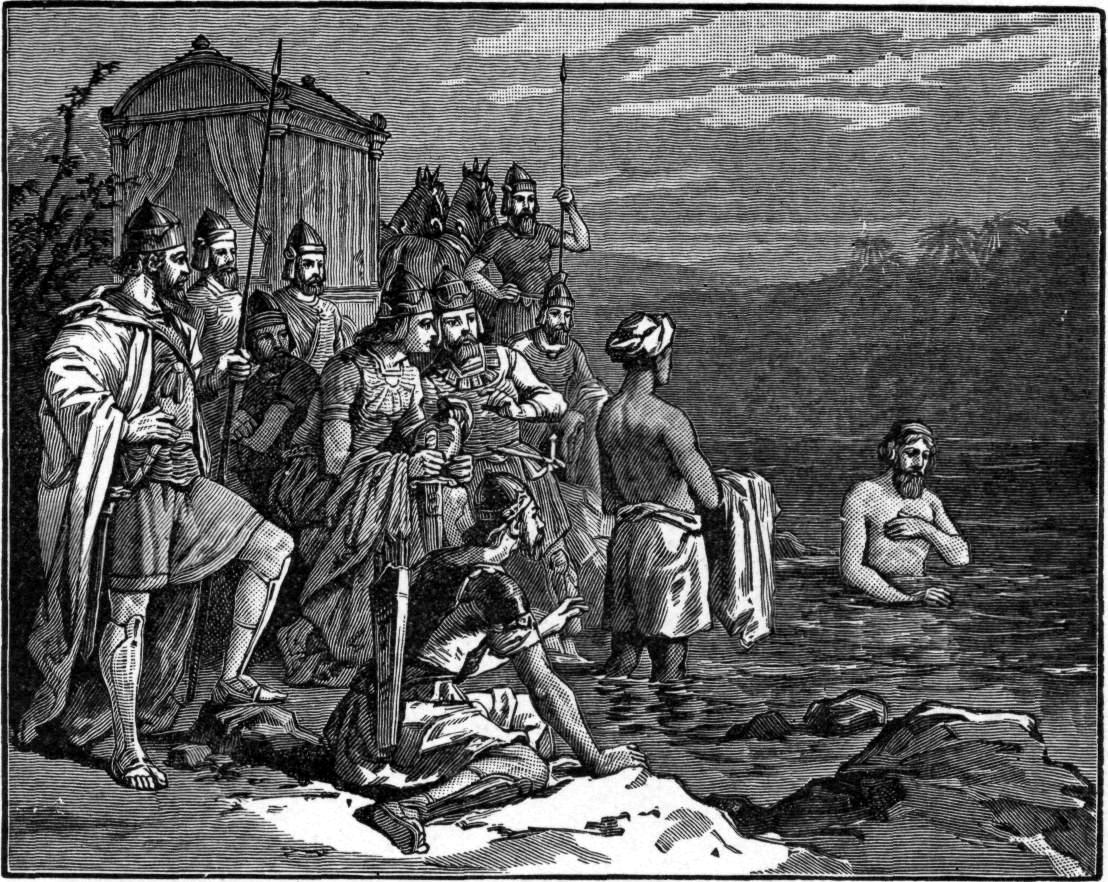

Firstly, there is the value of keeping things simple. Naaman was commander

of the king of Aram’s

army. Aram was part of what is now Syria. We

are told Naaman suffered from leprosy, but whenever leprosy is mentioned in

the Bible, it can refer to any one of a wide range of skin conditions.

Whichever one it was, it was obviously causing Naaman some distress, and he

was desperately seeking a cure.

Naaman expected Elisha to come out and perform a miracle and seemed quite

offended when a messenger came out instead and told him simply to wash seven

times in the Jordan, whose water was to him quite inferior to that found in

the rivers of Damascus.

Naaman had tried to over complicate things. But on the advice of his

servants, he calmed down and kept things simple by doing what

Elisha had originally asked. And he was cured.

Secondly, established social structure can be inverted in the bigger scheme

of things. While Naaman had faith that Elisha could cure him, this

originated from the word of someone at the very bottom of his society: a

little Jewish servant girl.

Thirdly, faith requires action. It wasn’t simply enough for Naaman to

believe Elisha could cure his affliction. He had to do something about it.

Today we also heard a reading from the Holy Gospel according to St Mark, in

which we hear about a leper to comes to Jesus to be cleansed, and thanks to

his faith. There is much we could learn from this simple story. But hearing

the story of the healing of Naaman before it adds a great deal of depth and

enhances its theological richness. Imagine hearing this without having heard

the story of Naaman first, it would be a bit like watching television in

black and white instead of in colour.

So my message for today is that if you are going to read and study

scriptures, don’t forget the Older Testament. Not only does it pave the way

and provide context for the Newer Testament that follows, but it is well

worth reading in its own right.

Especially while we are preparing for Lent. Just like the first instalment

in a trilogy sets the scene for the rest.

Darryl Ward

11 February 2024